Normandy 3: The Airborne City & Utah Beach

- Tango Sierra

- Sep 17, 2023

- 14 min read

Updated: Sep 18, 2023

***POPCORN POST*** Sorry for the long break in posts, everyone! The job out here got busy in July and August. Without further ado... my adventures in the Utah sector!

Sainte-Mère-Église

After Pointe du Hoc, we continued to our first stop in the Utah sector and our sixth stop of the day for lunch, Sainte-Mère-Église. The city was small and overwhelmingly themed with American airborne memorabilia, photos, and trinkets. It was apparent that this place, perhaps more than any other stop we visited during the tour, was tightly grasping to its historical significance during the war. It adopted not only the cultural feel of American exceptionalism, but the niche military culture of Army Airborne exceptionalism. Many buildings were painted red, drab green, or navy blue. Here, active duty or retired military members wearing 82nd Airborne Division or 101st Airborne Division insignia are instantly part of the WWII airborne legend; they are simply more recent extensions of the historical greatness achieved by these units across the Utah sector in 1944.

There were lots of options for lunch, several cafés, a pub, and a couple kiosks selling fast-grab items. Guillaume warned us to avoid one restaurant where the owner was unfortunately known for rudely yelling at American customers. Don’t have to tell me twice. I opted for a small place called Creperie Cauquigny. I ordered one savory crepe and one sweet crepe. The savory one was a wheat crepe with goat cheese, walnuts, and honey drizzled on top. The sweet crepe had a fantastic lemon curd on top. Both were large and delicious, and the owner was incredibly nice.

After lunch, I headed to the Airborne Museum. Entry was included with the tour, I had to give the tour name and a password that Guillaume relayed to us before leaving the van. The museum had multiple facilities and outdoor displays. It was a full sensory and immersive experience. There were videos, photos, and parachute objects galore on display. There was even a holograph presentation designed to inform guests about the D-Day airborne operations.

The holograph briefing of the airborne operations in the Utah sector. Can't see it but he has a cricket in his hand and is demonstrating it. You can only imagine what would happen with these in a room full of 18-24 year old men... and that's exactly what happened during this presentation... all the clicking!!

The holograph was an officer projected onto a stage talking to the audience as if they were paratroopers preparing to jump on 6 June. He explained the timing of the operation, the employment methods of 800 gliders and C-47 aircraft being used to drop 13,100 soldiers into six drop zones and one glider landing zone, and some of the equipment they were given to aid them in getting to their rendezvous points once on the ground during pre-dawn hours, most notably metal clickers called crickets.

Crickets were square tubes made from thin sheets of metal. They were approximately three inches long, just long enough to be securely grasped but also concealed in the palm. One wall of the tube had a circular depression at one end and was left partially unsecured at the other. When the unsecured end was pressed, the circular depression would flip inside out to make a metallic popping noise. At a distance, these sounded like a loud cricket chirp. Crickets were used determine friend from foe and communicate amongst friendly forces in the dark, without using a light source and giving away American troop positions. Once safely on the ground, paratroopers would click their cricket one time. If they heard a double click in return, an airborne ally was within earshot. They could then continue using this method to navigate closer to one another, assemble in large numbers, and progress toward their operational objectives.

The airborne operation was the first phase of D-Day, beginning at midnight on 6 June. As previously discussed in this blog series, it was critical they catch the Germans by complete surprise. The ideal outcome for the airborne operation was to cut off the Cotentin Peninsula, making it easier for the Allies to secure the deep water port at Cherbourg. Crickets gave the Allies a head start in the effort to isolate Cherbourg and ensured the Nazi’s would be caught off-guard by the beach landings six hours after the airborne force was already on the ground. For me, the holograph experience included an amusing realization that while we have made vast advancements in technology, the tone and style of a military briefing has not significantly changed in 80 years. Overall, it was quite impressive.

As for the rest of the museum, I only had an hour to explore, and it wasn’t nearly enough time. There were immersive displays that attempted to give guests an idea of what it was like inside and while jumping out of the C-47s and gliders as well as conditions on the ground when paratroopers landed in St-Mère-Église. I was shocked to discover how “flimsy” gliders were, literally nothing but canvas stretched over a wooden frame. Yet they held 10 people, two in the cockpit and eight in the fuselage, plus all the airborne kit and/or an anti-tank gun. They did the job and put significantly less demand on the war industry than other aircraft.

I can confirm this is precisely what sitting in a cargo plan looks and feels like. The difference in the above and below pictures is kit on in 1944 versus kit off in 2014 (my C-130 ride to Afghanistan, I am basically sitting on my helmet and body armor. I also was not intending to parachute anywhere).

Glider hangar facility that was overall shaped like a parachute! This glider was huge, but was essentially made with dowel rods, plywood, canvas, paint, glue, some 550 cord, and maybe a couple screws. You can see the wind screen with the pilot/co-pilot at the front, and then eight passengers, four in the front half of the fuselage and four in the back half of the fuselage.

Simulation of the ground conditions in town after paratroopers landed.

After the museum, we met back up with the tour group and stood outside the church at the center of the town. Here Guillaume showed us some of the D-Day damage and explained some of the major events that occurred between midnight and dawn. Around midnight, unbeknownst to the Allies, a house near the center of town caught fire. When the first paratroopers began jumping around 0100, the town was partially awake trying to suppress the fire. The paratroopers were much more visible to the Nazis than they ever wanted or planned during their descent. The Germans quickly engaged the Allies, and subsequent waves of airborne found themselves descending into a raging small arms fight.

Two of the paratroopers, John Steele and Kenneth Russel, got their parachutes snagged on the structure of the town church. A third paratrooper, John Ray, landed on the ground at the foot of the church’s main doors and a fourth, Ladislav Tlapa, got tangled in a tree nearby. A Nazi soldier quickly approached the front of the church, opened fire with his side arm, and hit Ray in the midsection. Ray collapsed. The Nazi walked by him and then took aim up at Russel and Steele. But before the Nazi fired again, Ray pulled his Colt 0.45 and shot the Nazi in the neck, killing him on the spot and saving Russel and Steele. Russel, who watched all of this from his suspended position above the church’s main doors, hurried to cut himself loose and come to Ray’s aid, but Ray had succumbed to his abdominal wound. Russell noted that Steel and Tlapa were both still suspended and hanging lifeless, so he moved to find cover and proceed with the mission.

*This is not my photo, but depicts the positions (from top to bottom, left to right) John Steele, Kenneth Russel, John Ray, and Ladislav Tlapa.

A dummy hangs from a snagged parachute on the most visible side of the church; Guillaume explained this was meant to represent John Steele, although he was actually suspended on the opposite side. Nicks from bullets are still visible in the blue iron fence.

Tlapa was indeed dead, but Steele was feigning. Prior to the Nazi showing up, Steele had attempted to cut himself free and dropped his knife. Steele was later retrieved alive by two Nazis that climbed the bell tower and pulled him up to take him prisoner. He escaped from the German POW camp after a couple weeks and went on to fight in the rest of the war. John Steele is, by far, the most well-known of these four men. He is the one portrayed hanging from the church in the movie The Longest Day, and his notoriety is no doubt due to this Hollywood depiction of events. However, in his fame, John Steele never really acknowledged that any of the other men were at the scene. If you ask me, John Ray’s actions were what made the story worth retelling and Ray undoubtedly saved Steele’s life. After Guillaume’s retelling, we briefly went inside the church to look around, then met back at the tour van and proceeded to a monument that honors the Battle of La Fière Bridge.

La Fière

We drove west from Sainte-Mère-Église and stopped in a gravel pullout on the side of the road at La Fière. The area is so unassuming, it cannot even be called a town. There was only a manor, a church, and a few other small buildings sitting in a low-lying agricultural area. The road ran right beside the manor, became a little stone bridge crossing a small creek, and then continued straight west to disappear in a small ridge of trees. I could see the creek was no more than 4-5 feet across. But Guillaume began his explanation at the La Fière memorial site by telling us that in 1944, the Nazis had deliberately dammed it to flood the entire low-land, effectively turning it into a mile-wide marsh. In Army terms, marshes are “restricted terrain” and are operationally avoided at all costs. The flooded plain made this area impossible for people or vehicles to traverse. The elevated road and its little stone bridge became the most effective way to progress west from St-Mère-Église; other routes ran too far north or south to ensure Allied success in severing Nazi control of the Cotentin Peninsula.

In the early morning hours on D-Day, a company of 82d Airborne soldiers managed to land in their designated drop zone and navigate to their objective at La Fière bridge. After a few skirmishes with German machine gun defenses during initial reconnaissance efforts, the Americans were in control of the bridge and fully set to defend it from the eastern bank by 2:30pm. They were armed with their standard M1 rifles, a couple types of grenades, one 57mm anti-tank gun (small artillery really), three bazooka teams, some mines placed in the road on the western side of the bridge, and a handful of mortar teams but with minimal mortar munitions.

Once American defenses were set, three tanks appeared from around the bend in the road, headed for the bridge. They began pummeling the company with tank cannon and mounted machine gun fire. As the tanks approached within 50 yards of the bridge, bazooka teams and the anti-tank gun crew quickly knocked out the first two tanks, with the third tank becoming crippled soon after. This first hard German counterattack left the bazooka teams low on ammunition. On the subsequent resupply run, the battalion commander and the operations officer (a Major/O-4 and a Captain/O-3, respectively) were killed. A first lieutenant (O-2) within the company became the battalion commander, Lt John Dolan. Throughout the night, the company suffered steady casualties due to persistent German mortar and machine gun fire.

The morning of 7 June, the German’s incoming fire thickened, signaling the start of another hard counterattack and causing American personnel to shift positions. In the process, there was confusion and miscommunication over the manning of the anti-tank gun. The gun crew caught a rumor that Americans were retreating (rather than simply repositioning) and they abandoned their post. Shortly after, four more tanks pushed around the bend, steadily thundering down the road. The Americans returned heavy fire, but Lt Dolan suddenly realized he didn’t hear any 57mm fire. He ran to the gun and discovered it unmanned and missing its firing mechanism (standard protocol so that if it fell into enemy hands, the Germans couldn’t use it against the Allies). Dolan began hurriedly organizing the small number of soldiers nearby for an alternative grenade attack. Due to the type of grenades they had available, Dolan realized their only chance of succeeding was to allow the tanks to cross the bridge, physically run up to them, and place the grenades on the tanks. In this critical moment, two breathless privates suddenly reappeared at the anti-tank gun position with the firing mechanism. Minutes later, anti-tank rounds rained on the two lead tanks and stopped them before they crossed the bridge. The remaining pair of tanks rapidly retreated.

Anti-tank gun at La Fiere.

With the road now well-blocked with a total of five inoperable tanks, Lt Dolan managed to return to the battalion command post about 150 yards east of the bridge. Unable to drive vehicles through the tank graveyard, the Germans began alternating waves of infantry with waves of artillery and mortar fire. This continued to devastate the company, particularly First Platoon, who only had 15 men left and was being commanded by a sergeant named William Owens. At one point in the afternoon, a runner appeared to check on Owens and inquire about the company’s status. Owens said he was scavenging for bullets from their deceased soldiers and requested reinforcements or retreat. The runner returned to the command post and reported the information to Lt Dolan. Dolan wrote a quick note and told the runner to deliver it to Owens: “I know of no better spot to die. We stay.” Owens and his men stayed. Not much later, the Germans ceased firing and appeared waving a Red Cross flag with a request for 30 minutes to tend their wounded. The Americans quickly agreed, and a half hour turned into two hours. Night set in and light German artillery resumed.

Around 0200 on 8 June, Owens heard the Germans using a tank to clear a path through the tank graveyard. He stealthily approached, got within 40 yards, and then threw a grenade that didn’t hit the active tank, but exploded close enough that the Germans instantly reversed and hightailed it out of range. This was the last German attempt to take La Fière Bridge.

The aftermath along the road west of La Fiere Bridge.

Later in the day on 8 June, Lt Dolan and the rest of the company were relieved from their positions at La Fière with a total of 68 casualties: 17 dead and 51 wounded. Of the deceased, seven were killed manning the anti-tank gun. The two privates that returned to the anti-tank gun with the firing mechanism were awarded Silver Stars. Four grenade team members were awarded the Distinguished Service Cross. Sergeant Owens was also recommended for a Distinguished Service Cross but it wasn’t approved; he was later awarded a Silver Star for similar actions during Operation MARKET GARDEN.

The company overall succeeded in seizing the bridge and enabled the Allies to push quickly west. Guillaume also mentioned a video produced by The History Traveler about this battle. I watched it later and it was very well done. There is a phenomenal bronze table/diorama that depicts the battle in front of the memorial statue, and when I walked around the front, I saw the table appears as if it’s draped with an airborne parachute.

The bridge and the manor are just off to the left. The little hedgerow directly in front down the slope of the hills is where the creek runs.

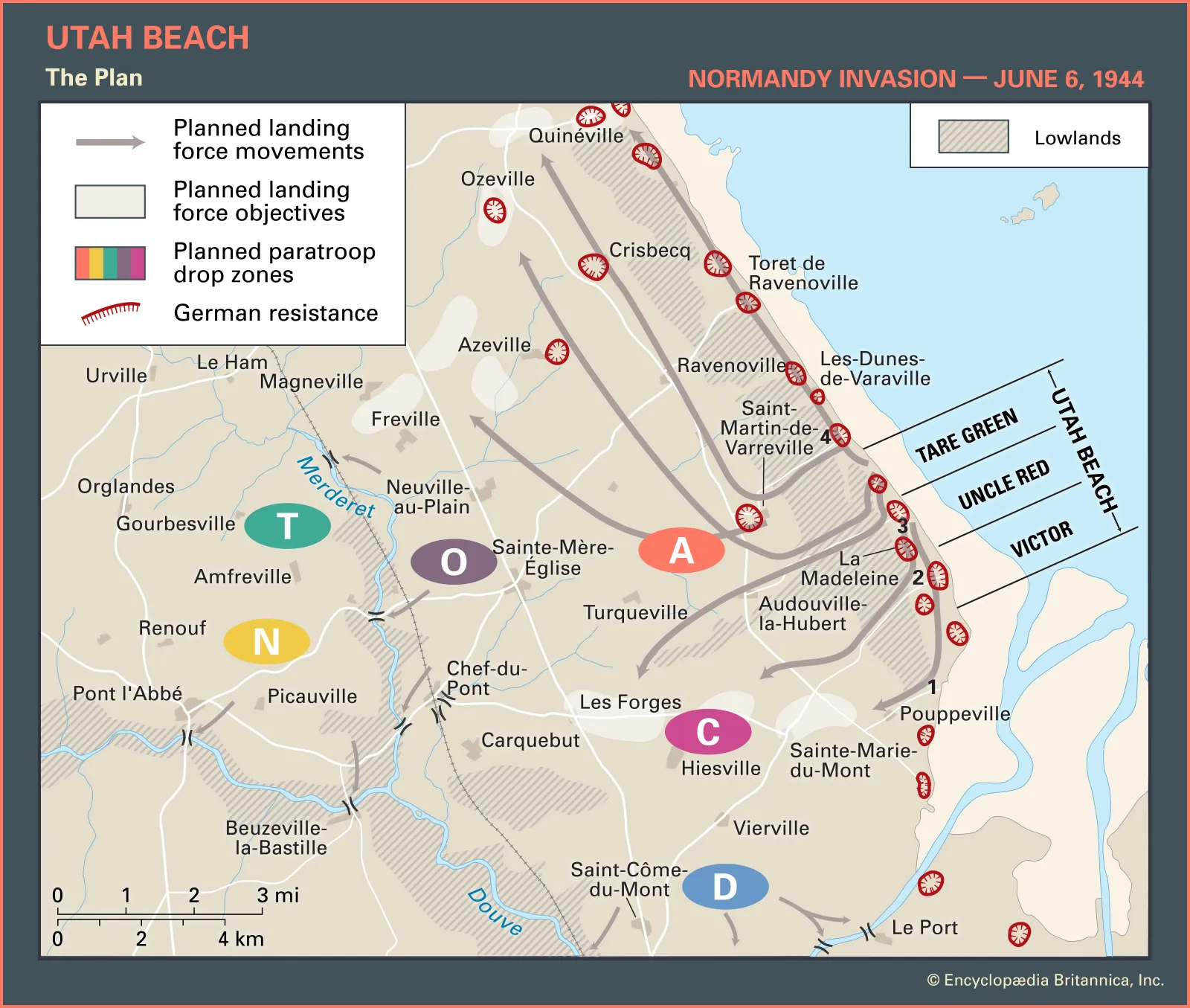

Utah Beach

After La Fière, we went to the Utah Beach head. Guillaume showed us where the German headquarters was located, a concrete bunker on the backside of the beach that they painted windows on to try and fool the Allies into thinking it was a house. The original paint is still visible today. We then went onto the beach and discussed events/landmarks there:

800 German soldiers (200 less than Omaha)

10K strongpoints (5K less than Omaha)

Air support was B-26s instead of P-47s and P-51s, so planes were able to get below the clouds and had much better success hitting German strongpoints ahead of the landing assault. This helped account for fewer casualties.

There is only one landmark on the beach, a house overlooking the water that the Germans used as a Command Post and still stands today.

21,000 American soldiers landed on Utah (13,000 less than Omaha)

197 American casualties on the beach (about 2,200 less than Omaha). But of the 14K airborne troops, there were 2,500 casualties, bringing the Utah sectors total American losses to 2,700.

Landing craft were actually made of wood, but a steel replica sits on the backside of Utah with a statue of personnel running out. The running Allied personnel are each carrying a different weapon (American, British, and Dutch) to recognize the three main nations that participated in the Utah landing.

The house the Germans used as their command post is in this photo, but it's so distant it's impossible to make out.

After the beach, Guillaume drove us by the statue of Lt. Richard Winters for a quick photo opportunity before moving on to our last destination of the tour: Angoville-au-Plain. If you don’t know who Richard Winters is, watch the mini-series Band of Brothers (now on Netflix!), but in a nutshell he was the commander of E Company and eventually 2nd Battalion within the 101st Airborne. His awards include a DSC, two Bronze Stars, a Purple Heart, a French Croix de Guerre, and a Belgian Croix de Guerre. He was also nominated for a Medal of Honor, but it wasn’t awarded.

Angoville-au-Plain

In this tiny town, two 101st Airborne medics named Robert Wright and Kenneth Moore initially found themselves isolated from the rest of their unit in the early morning hours on D-Day. They individually entered the town at different times, but both came upon injured French civilians that had been caught in the German-American cross-fire. Wright arrived first and set up a treatment site inside the town’s small 12th century church by pinning a red cross insignia to the door. Moore found Wright in the church shortly after. They then started running into injured American soldiers and brought them into the converted aid station. Later in the day, armed German soldiers walked in and saw the two medics treating people. They asked if Wright and Moore could treat their wounded. The medics agreed, but said anyone wanting to enter had to completely de-arm. The Germans agreed, turned around to drop their weapons and ammunition outside, and began transferring their wounded into the church.

Wright and Moore continued to treat German soldiers, American soldiers, and French civilians for three days straight before the town was fully controlled and liberated by the Allies late on 8 June. The town changed hands between the Germans and Americans roughly three times in that 3-day period. Other interesting facts:

The church was hit by two mortars. One fractured the ceiling and the subsequent falling debris injured Wright’s head. The other later penetrated the roof and impacted the floor. It cracked the floor tile, but miraculously did not detonate. Wright quickly picked up the unexploded ordinance, threw it out the window, and kept working. The patched hole in the ceiling and the smashed tile are still visible today.

They used a hand cart from a farmer to go out and retrieve wounded personnel, transporting them back to the church for treatment.

Several pews are still blood-stained from patients.

They consistently had to ran out for fresh water from a nearby well (even when the area was under German control)

Unbeknownst to Wright and Moore, the church is named L’eglise Saint-Come-et-Saint-Damian, after its two patron saints, Cosmas and Damien. Legend has it this pair of Arabian martyrs (presumably brothers and allegedly twins) were known for their exceptional healing skill and Christian-based mercy in the 3rd century. Cosmas and Damien treated anyone for free, regardless of race, gender, ethnicity, nationality, allegiance, or faith. Today they are generally considered the patron saints of medical professions and twins.

After Angoville-au-Plain was liberated, it was discovered that three German soldiers were hiding in the church’s steeple the entire time it was used as an aid station.

Several of the stained glass windows were knocked out during the war. They were replaced with images honoring the American airborne paratroopers from D-Day.

Both Wright and Moore survived the war and were awarded Silver Stars.

Wright had his ashes split after he passed. Half were scattered from a plane in the U.S. The other half was buried in the Angoville-au-Plain church cemetery. This was technically against French law, but Wright was very good friends with the mayor, and the mayor made it happen.

It was amazing and extremely humanity-affirming to be in this church. The divine serendipity of Moore and Wright using this particular church to set up an aid station was not lost on anyone in the tour group. Overall, the two medics were credited with saving 80 lives inside the sanctuary. Aside from standing on Omaha beach, it was my favorite stop of the day.

From Angoville-au-Plain, we made a 40-min drive back to Bayeux. Our tour ended at 6pm, an hour over the projected end time, but the entire group was very grateful to Guillaume for his patience, knowledge, and assistance in making the tour special. It was a long and exhausting day. I found a place to eat dinner in Bayeux and then walked to my hotel about 20 mins away, arriving just before 8pm. I had a little trouble locating reception because it was in the restaurant and the barkeeper was also the concierge. I checked in and then crashed for the night in preparation for Paris the next day.

As always, thanks for taking time out of your day to follow along! Here's that video about La Fiere Bridge, it'll show you more of the area that I apparently forgot to take photos of... like the actual bridge: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8iKq4l0mg4M. Whoops.

Fun closing fact: Brigadier General Theodore Roosevelt, Jr. led the Utah beach invasion. Upon realizing they had landed much too far south, he famously remarked “We’ll start the war from here!” Three hours later, all Utah draws were secured and by the end of the day the division was only one mile from Sainte-Mère-Église.

Tango Sierra out!

Comments